The view from Stuttgart: On Cognitive Dissonance

January 17, 2018

A slight change this week in that I will get straight to the point in the first paragraph. And the point is this. We increasingly live in a world, some us us help create a world, driven or steered at least, by models and algorithms that emulate the cognitive processes we use for decision making. A polarisation of opinion ensues in public debate (hence dissonance, within the public perception as a whole).

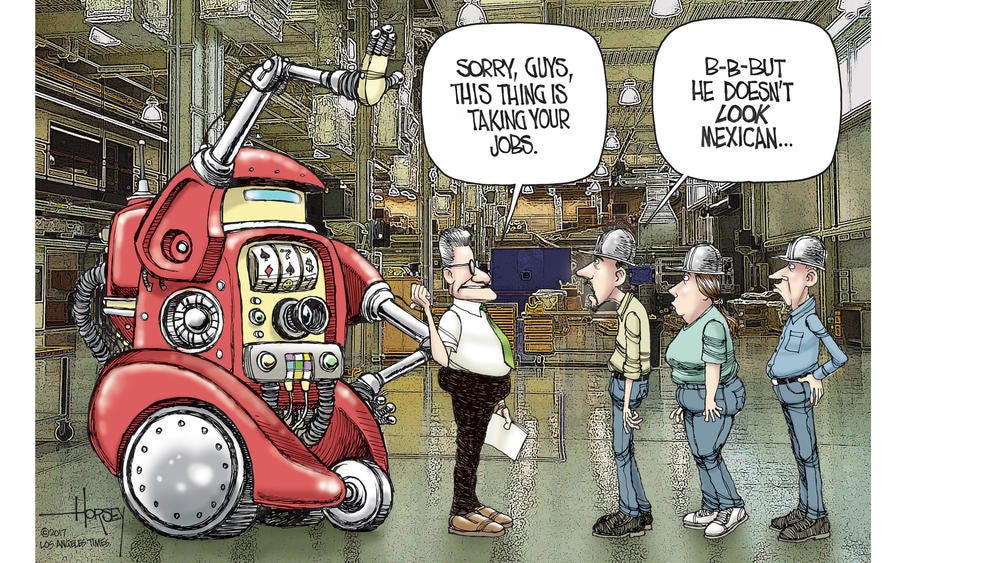

In one camp – those that say, ML, AI and machine based decision making is more consistent, cost effective, usually more accurate. Certainly they are faster than the humans they replace or assist.

In the other, those that say we are being taken over by robots, Terminator is around the corner. They caution on mass unemployment encompassing not only skilled manual workers but the white collar and knowledge workers too who had previously assumed they would be immune from “automation redundancy”.

So there is a society wide angst driven by this underlying dissonance in perceptions akin to the shock you have just before a car crash (as well as just after, if you are lucky). Or at a minimum the confusion when you have found that either you have driven home rather than to the fitness studio without realising. Or maybe you ended up at the supermarket when your wife is expecting you to take her out for a meal. You just cracked that pressing work issue on the way, but that doesn’t impress your wife. Never happens to you? Well I am afraid, in on it does.

Expectedly the truth is somewhere in between. And the dissonance is healthy. It forces an arbitration between the poles where the arbitration process has been honed over epochs of evolution (in the real-time scenario) and further by millennia of cultural development the rest of the time in the case of humans.

As we have discussed before although our consciousness and sits us behind virtual-reality specs which give the impression that there is a rational, sentient, being taking well-thought out decisions based on objective fact, the decisions in the real-time case are usually taken before we are aware of them. Either they are based on the assembled past experience of the “I” which has occurred so often it has become part of the neural-network weighting. Or they the are part of the neural-network weighting via the genetic, evolutionary path.

Neither produces a perfect system. As with any process we should apply CiP, (continuous improvement driven by continuous learning,) to ensure that the decision is state of the art. As individuals, this depends on learning from our mistakes and being willing and able to communicate that learning to friends and colleagues. Whether that happens in an organisation, or not and whether or not is successful is an organisational, cultural and therefore a senior-management issue.

Now we start to apply these processes – based on a model (good or bad), driven by an algorithm, to process automation (Industrial Automation, Workplace Automation, Autonomous vehicles or otherwise).

I say “now” but this is nothing new and there is a sense of history repeating itself over and over again, albeit in slightly different ways. The core issues strike me as being identical.

Starting with highly repetitive tasks that can be mechanically automated. Steam-driven looms for cloth, industrial automation, electronic engine management, financial modeling and products based on these models (CDS for example) to automated driving systems and automated decision support in white-collar processes, all take an existing manual process and automate it employing a particular technology. This is universally accompanied by cultural resistance famously illustrated by “the Luddites” 1

Yet in the case of the latest round of technology-angst, we see the same concerns. A reluctance to acknowledge the unlikelihood of the technology disappearing back into the box. And unfortunately a repetition of the same mistakes. The result has been children being killed as they dart between looms whilst retrieving the shuttle, nuclear accidents, chemical leaks (Union Carbide in Bhopal is a gthe boys to football practiceood example), the diesel scandal, stock-market crashes.

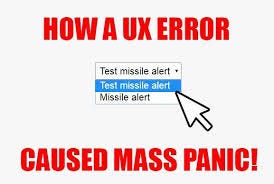

The mistake is this. By introducing automation, you usually create an immediate and seductive economic benefit. But you embed and/or amplify any existing faults in the human-driven process. On top, you introduce the opportunity for new, unforeseen faults because the automation failure-mode may be far removed from familiar failure-modes in the existing process.

There are some very well-known mechanisms to resolve, illuminate or avoid these issues from computer-science and the interface between computer science, software development, psychology and … economics.

Byzantine fault-tolerance for example, based on the Byzantine Generals’ Problem is implemented in Blockchain to verify validity as well as on the control system of the A380 2 or bitwise arbitration on the CAN bus for example 3.

The Human race, despite a huge talent for discovering things – has an almost equally vast talent for forgetting about them or ignoring them because they “weren’t invented here”.

So let’s take three examples to illustrate. Then then we can apply some of the learning to white-collar process automation, autonomous vehicles and some other areas.

1) Union Carbide in Bhopal

2) The 2008 stock market crash

3) The diesel scandal

1) Bhopal

Here we have a chain of examples to choose from. We will take one. A manual process for managing pressure in chemical storage tanks was automated, leaving humans to intervene when an alarm sounded.

a) Faults in the existing human process were replicated resulting in a fixed control algorithm without a human “brain-in-the-loop” to rectify the control strategy on the fly.

b) The result: frequent false alarms.

c) Failure to intervene because the assumption of a false alarm had become the default arbitration result, based on human experience.

The boy who cried “wolf!”4

That’s one of Aesops fables. In other words – not exactly headline news for humanity.

2) The 2008 stock market crash

Also provides multiple examples:

a) Market models predicted rising house prices when they in fact fell

b) The model used for the sales process incentivised widespread abuse by salesmen overselling mortgage products to people who had no hope of repaying the loan

c) The model used for derivative pricing was flawed. The flaws were widely known but ignored or poorly understood both by senior financial managers and the clients of the products (CDS). So CDS were also widely mis-sold or mis-used.

d) The result: massive over-leveraging of the mortgage market and industry wide exposure to poorly assessed risks embedded within a widely-used product.

Again lessons-learned from engineering safety-critical systems were not applied to financial engineering. Risk assessment was woefully inaccurate as a consequence. (Other factors my have applied)

In an interesting twist, there is a new tussle over the market for CDS (which is understandably declining despite the product having its uses)5. Again this illustrates that lessons have neither been learned, nor is a functioning mechanism for continuous improvement to allow abuses of the market to be curtailed.

3. The diesel scandal

Illustration of how discrete parts of a system can work perfectly well and lead into a emergent error-state.

a. In the late 80’s & 90’s many previously mechanically operated controls were replaced with highly optimised software driven control functions offering greater reliability, reduced manufacturing costs, reduced cost of ownership and the possibility to significantly improve fuel consumption and emissions.

b. Government legislation worldwide assumed that the potential of these technologies would be employed by car-makers and consumers expected the same.

c. The models for driver behaviour during emissions testing did not adequately reflect real driving conditions

d. Unsurprisingly control algorithms were optimised to the behavior expected by the models used during the test phase. Different control algorithms or calibrations could be applied outside of the test environment. (This is a simplification but I need to clearly illustrate the point)

e. The mechanical hard-wired past behaviour of engines was assumed by the market. The incomparable flexibility of the new systems to increase risk as well as to reduce it was ignored.

f. An incentive emerges to ignore any lack of feedback between teams or individual engineers working on product-performance or conversely compliance AND any feeback from these teams to management that there might be an issue

g. A financial incentive emerges to trick the market by heavily optimising at the extremes of Real-life vs legislative model.

Again this looks superficially and generally nasty behaviour. And polarised opinions in the industry.

Yet it is the result of a combination of well-known issues. An emergent failure state emerges. Functional algorithms are adopted having been optimised for a development model. There is a divergence between the assumed model and real-life behaviour. Without an in-built mechanism to continuously align the development model with real-life behaviour, ensuring that the optimal (A model combining full compliance with legislative requirement but providing best possible performance) is continuously applied, even when the situation suddenly changes, disaster ensues.

There are two very noble reasons for optimising on the extreme positions. a) Making the best product for the customer b) Complying with legislation. But unless the two are considered in context with an appropriate arbitration between the two, unforeseen risk emerges.

If you think you are driving on compacted snow and suddenly you find yourself on a sheet of ice. There will be a car-crash.

There is an established and mature base of both academic literature and industrial experience with cognitive dissonances at the human-machine interface when it comes to automating mechanical, manual, administrative functions. Human functions of virtually any kind, in fact, in the wider context 6 7. This base of knowledge is also being continuously improved – from Rasmussen & Reason through Leweson to Tim Kelly at York 8 Yet we still make basic mistakes in HMI design, system design & organisation process development.

Not to mention risking a war.

With regard to white-collar process automation this has been highlighted on LinkedIn during the course of writing. And of course there are a wealth of other examples some of which we have all seen on LinkedIn and in the general media. 9.

The Hiring process is broken! B. Hyacinth

In relation specifically to the topic of human-resources automation, screening of applicants CV’s for example, one of the comments was short, interesting and too the point. I’m paraphrasing, but “Well, what are you going to do about it?”. Somehow this illustrates exactly the what the current (public) debate is missing. We are presented with the argument but not the arbitration. So Robots will take our jobs. Well qualified people will be left on the scrap-heap. Or not!

It reminded me of a piece by a Russian absurdist from the 20’s, Daniil Kharms10 called “Optical Illusion”

Semyon Semyonovich, with his glasses on, looks at a pine tree and he sees: in the pine tree sits a peasant showing him his fist.

Semyon Semyonovich, takes his glasses off, looks at the pine tree and sees that there is no one sitting in the pine tree.

Semyon Semyonovich, puts his glasses back on, looks at the pine tree and again sees that in the pine tree sits a peasant showing him his fist.

Semyon Semyonovich, with his glasses off, again sees that there is no one sitting in the pine tree.

Semyon Semyonovich, with his glasses on again, looks at the pine tree and again sees that in the pine tree sits a peasant showing him his fist.

Semyon Semyonovich doesn't wish to believe in this phenomenon and considers it to be an optical illusion.

Of course cognitive dissonance is one of the main mechanisms for Humour too. I have always thought it a bad idea to explain a joke, since if you do you remove the humour (by aligning the model within the joke with the model of the world being employed by the audience) but as early 20th Century Russian absurdist literature is a long way removed from safety culture maybe it is worth doing in this case.

Semyon Semyonovitch is confronted with two possible models of reality. The outcome of the first is unsurprising. The second model outputs an unpleasant and highly improbably result. Semyonovitch has an in-built arbitration in the case of improbable visions which is essentially a “fail-safe”: Nothing improbable and unpleasant can exist – therefore ignore.

The point of course, is that we have a long history of understanding that these dissonances arise and we have a solid basis for their resolution. So to answer the commentators comment. Take our experience and apply it appropriately. Whether this happens or not is the issue. This ducks the question of potential future Black Swans (pun intended!), but there are models and methods to cope with those too. Even if events overwhelm them we know that we need a continuous improvement process – the only question is ensuring it happens and is effective in implementation. So the pressing problem is not whether Robots will take our jobs or not. Or whether they will suddenly become conscious and decide to remove their makers. It is whether we will design them and manage them appropriately so that they do not kill us by accident.

Footnotes:

1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luddite.

2 Byzantine fault-tolerance for example, based on the Byzantine Generals’ Problem https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_fault_tolerance http://marknelson.us/2007/07/23/byzantine/

3 https://elearning.vector.com/index.php?&wbt_ls_seite_id=490341&root=378422&seite=vl_can_introduction_en

4 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Boy_Who_Cried_Wolf

5 https://www.ft.com/content/69194bda-f5af-11e7-88f7-5465a6ce1a00

Blackstone, a hedge fund, has offered refinancing to a housebuilder, which is in a recoverable but unhealthy financial position. The refinancing package depends on the house-builder defaulting on its existing debt. Blackstone holds a high-risk position on CDS that have an extremely high value given a default – so they would be able to offer an excellent refinancing solution to the house-builder. And a tidy profit. The rest of the market would lose because of an artificial default event on the part of the housebuilder which is only triggered because the refinancing party will gain from the house-builder not repaying its existing creditors. So the general market assumption – ie that a very large, stable house-builder will be credit-worthy is being subverted by a completely legal but unforseen event in the product model. Namely an artificial default, incentivised by instant financial gain by a single hedge fund and the debtor itself. This is nasty, but also should lean to lessons learned that improve the behaviour within the market – if not the product will probably die, if not now then after a few more nasty shocks.

6 Reason’s model of Human Error https://books.google.de/books?hl=en&lr=&id=WJL8NZc8lZ8C&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=Error+Model++Reason&ots=AmNl1c8i3d&sig=-W7TyytO2xIpUju8Chw-UUSyv2M#v=onepage&q=Error%20Model%20%20Reason&f=false

7 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jens_Rasmussen_(human_factors_expert)

8 https://www-users.cs.york.ac.uk/tpk/

9 https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/robots-take-your-job-brigette-hyacinth/

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08v8p14

http://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-the-papers-42498785

10 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniil_Kharms

Further Sources & References:

http://sunnyday.mit.edu/

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Figure-1-Rasmussen-s-dynamic-safety-model-illustrating-how-a-system-can-operate-safely-inside-t_257350911_fig1

https://books.google.dk/books/about/Information_processing_and_human_machine.html?id=rKUoAQAAMAAJ

Festinger, L. (Ed.). (1964). Conflict, decision, and dissonance (Vol. 3). Stanford University Press.

Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58(2), 203